Social media is a blessing and a curse. On one hand, it lets us connect with people all over the world and stay in touch with the friends and relatives we might otherwise lose contact with. On the other, it can be a terrifying swamp of embarrassing photos and oversharing. But there’s one thing that it surprisingly isn’t. And that’s new.

How can social media not be new? How can it not require the Internet? In fact, analogue versions of LinkedIn and Facebook have been around for centuries. They existed in the form of paper books called alba amicorum, in which people collected messages and images from friends and colleagues. They’ve been around for hundreds of years. Dutch historian Sophie Reinders studies these fascinating pieces of history.

These books were used by young men and women in Northern Europe to record and keep track of friendships and professional relationships.

The practice is thought to have begun in about 1560.

Alba amicorum literally means “friend book” in Latin.

These books were used by both boys and girls, but because of how society functioned in the 1600s, they used them for different reasons.

Boys were routinely sent on tours of Europe to study at famous universities and institutions, and to meet with great thinkers and scholars. They used their friend books kind of like the way we use LinkedIn — as a way of gaining professional connections.

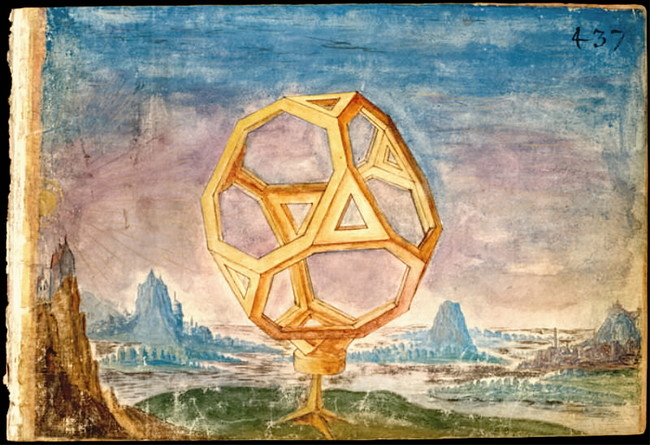

These images come from the book of Michael van der Meer, who recorded his travels with impressive illustrations.

Some images depict members of the aristocracy.

And he apparently spent time with pretty ladies.

This might be an early version of the “It’s Complicated” relationship option.

While boys toured the continent, girls were usually sent to spend time in convents or to serve as ladies-in-waiting, which helped them break into the best social circles. They didn’t travel much, but they still used friend books.

Instead of notes from scientists and artists, the girls’ books were filled with correspondences between friends and admirers, inside jokes, and detailed accounts of social events. If the boys’ books were like LinkedIn, then the girls’ were like Facebook.

Juliana de Roussel’s friend book was beautifully decorated as well.

This one belonged to Jacoba Cornelia Bolten, who was a socialite during that time period.

These books are striking in their similarity to Facebook — it’s just that the technology was a bit different. Pictures were drawn, and instead of sharing articles, they wrote down their favorite proverbs, song lyrics, and poems. Many women even wrote their own poetry.

Married couples could also “update their status” by writing a joint note. (That’s right. Joint social media was a nauseating problem back then, too.)

Pages like this one from Margaretha Haghen’s book show guests recounting their time at a party.

One passage reads, “In Shrovetide, on day two / We guests wrote this for you / And could not leave for home / So tipsy we’d become / Love made us so besotted / We left nothing in the bottle.” I guess things haven’t really changed that much.

(via MessyNessyChic)

These networks between people help historians develop a clearer picture of what life was really like during this time period. From the connections in their books, they can even piece together 400-year-old relationships.

Next time you want to complain about those darn kids on Facebook, remember that people have been posting silly things for hundreds of years. You can learn more about them on Reinders’ website, and through the National Library of the Netherlands’ digitized collection of books.